When building a website or an application, a lot of effort goes into making sure the application looks great, and that it is aesthetically pleasing. However, we tend to forget not everyone can interact with a computer the same way, and that some people have special needs.

Visually impaired people may not be able to appreciate your very well-illustrated website. People with motor issues may not be able to navigate as easily as you. People with mental conditions may experience sensory overload if your interface is too cluttered. And the list goes on.

These people don’t consume software the same way as the majority of people and have to fight every day against a myriad of problems with apps they use every day. Difficulties caused by lack of proper attention when it comes to making applications accessible.

Let’s deep dive into what’s accessibility all about.

What is Accessibility?

Accessibility (often written as a11y), is the practice of ensuring a maximum amount of people can access a website or an application.

For instance, take visually impaired people. These people have special needs and use specialized tools to help them browse the Internet, and interact with their computers. They heavily rely on screen readers to read what’s on the page for them and help them navigate.

We usually tend to think of accessibility as something special to people with disabilities. While they are concerned by accessibility and are a category of people who rely the most on it, they’re not the only ones who benefit from an accessible application.

How to make an application accessible?

There are a lot of things to consider when building an application, to make sure it follows all the recommendations and good practices when it comes to accessibility. I’ve compiled a small, non-exhaustive list of things to consider when building your app.

Carefully structure your document

Your document structure is extremely important, for many aspects including accessibility. By ensuring your document is correctly structured, you’ll enhance the way automated tools, ranging from screen readers to search engine crawlers, interpret your website and its contents.

Title structure

Titles are what give a rough overview of a page’s contents. You may be familiar if you’ve used text processing programs like Microsoft Word or LibreOffice with how tables of content are generated: they’re automatically created by looking at text that appears to be a title.

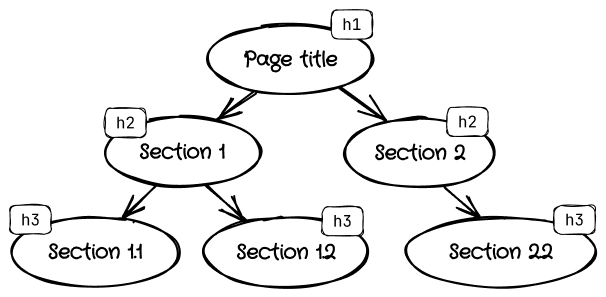

We have the same thing in HTML, except much more powerful, as we can explicitly declare what is a title and what’s its level, rather than relying on things like formatting. But we have to make sure titles are used correctly. My “cheat code” to titles is to see if my titles can create a proper tree structure, which follows the following simple rules:

- h1 is the root;

- descendants of h(n) nodes must be h(n+1);

- all titles must be part of the tree;

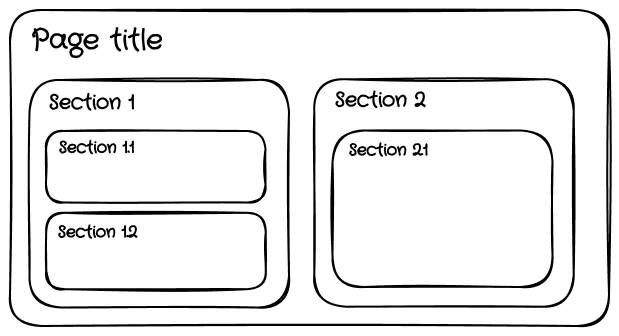

Take the following example “page”:

If we convert it to a tree structure, we obtain the following tree:

Which follows all of my rules. This page is properly structured! Of course, this isn’t a bulletproof test, but I find it quite good and effective to make sure your page follows good title hygiene. It possibly is a test that could be automated too.

While I do like the tree representation and my brain is good at visualizing these, you may prefer a linear list too. It’s probably simpler, but my brain somehow hates these… Whatever suits you!

Use all the elements

Your page should not be a soup of <div> elements. There are many tags at your disposal, that you should use!

Here’s an example of a poorly structured document:

<body>

<h1>My blog</h1>

<div>

<h2>Software posts</h2>

<div>

<h3>My software post</h3>

<div>Lorem ipsum...</div>

<div>Posted on January 2 by Cynthia</div>

</div>

</div>

<div>

<h2>Hardware posts</h2>

<div>

<h3>My hardware post</h3>

<div>Lorem ipsum...</div>

<div>Posted on January 6 by Cynthia</div>

</div>

</div>

</body>

We’re only using divs there, where we could do so much better. Here is the same document, but written with a lot more attention:

<body>

<h1>My blog</h1>

<section>

<h2>Software posts</h2>

<article>

<h3>My software post</h3>

<p>Lorem ipsum...</p>

<footer>

<p>Posted on <time datetime="2023-01-02">January 2</time> by Cynthia</p>

</footer>

</article>

</section>

<section>

<h2>Hardware posts</h2>

<article>

<h3>My hardware post</h3>

<p>Lorem ipsum...</p>

<footer>

<p>Posted on <time datetime="2023-01-06">January 6</time> by Cynthia</p>

</footer>

</article>

</section>

</body>

As you can see, this time there are 2 distinct sections, each section contains 1 article, the text has been wrapped

in proper paragraphs, the dates are wrapped in <time>, and the article footer is clearly defined now.

This may sound useless for you, as it doesn’t change the way your website appears. But remember, screen readers actually peek at the raw document! This greatly helps them make sense of your document.

Use semantically correct elements

This point sort of connects to the previous point, but differently: while using richer structures is better, it doesn’t render a website unusable. Using the wrong elements semantically wise does.

When you want to make a button, use a <button>. This sounds like common sense, right? Yet, an unbelievable amount

of websites use <div> with an onclick event listener on them. And yes, while it works, there is no way for a screen

reader to identify this div to be an actually clickable button.

Harm can be mitigated via some extra attributes such as aria-role, but at this point why not just use a normal button?

This also goes for elements that are used because of their default style: don’t. Use an element because it is the

semantically correct element to use. If you want a quote, use a <blockquote> element, and if you want it to look

big, do not wrap it in a <h*> block!! Style it with CSS! That should be common sense, yet this is an

unfortunately common occurrence…

Text and images

Now that our document has a proper structure, we need to make sure the contents of our structure are accessible.

Do not enforce a font size

There is no such thing as “one size fits all”. We shouldn’t consider font sizes as predictable, and should as much as possible ensure our applications respond to user font and zoom settings.

Units like 1em are the gold standard because these units adapt to the browser settings! A lot of people wrongly

assume that “1em = 16px”, and that they’re just another way to represent font sizes. This is false, it’s true for

the vast majority of people, but for some people, it may be 24px. And if our website uses em everywhere, everything

will scale accordingly!

For everything to scale, you should fully embrace the “font size is not predictable” mindset, and make sure your texts can properly wrap in all circumstances. This work should already be done if you have dynamic content, or if your application is localized to deal with the variable length of your strings.

Careful when picking colors

Contrast is very important. Text with improper color contrast may end up being completely unreadable for people who struggle to perceive color. Carefully picking the colors your text is written in, and ensuring a good contrast ratio is essential.

Colors aren’t sufficient to convey meaning either. While you may see a bright red error text, someone will see a text in a shade of grey and might not be able to perceive it’s an error message. The message should clearly be labeled as an error with an icon (properly labeled so it’ll be described by a screen reader), or more simply just by prefixing your message. Example: “Error: the reader is way too cute”.

In some color-heavy illustrations, such as charts, you should consider making sure colors are distinguishable by colorblind people, or that they use other features than color to convey meaning. For example, line charts may use different shapes of points and line patterns (solid, dotted, dashes, …), pie charts may use different patterns to fill each part of the pie instead of solid colors, etc.

Properly describe images

When your website has images, which it probably does, it must be properly described. And by properly, I don’t mean describing all images. Wait, what?!

Yep, that’s right. While most images should always be described, sometimes an empty alt attribute is the

correct way. The W3C Web Accessibility Initiatives describes a few cases in their

alt Decision Tree where it should be empty. This includes

purely decorative images, images already described by nearby text (or an appropriate <figcaption>), and some others.

The alt text should also not always be a description of the image, but should be the description of the function

the image serve for the case of functional images. I recommend you check the decision tree linked above.

Navigation

Navigating through a website is already sometimes a major burden for the “average” user: you probably already encountered a website with clunky navigation, where finding anything is a massive burden.

While this should be basic UX concerns, once you have a nice navigation scheme, you need to take extra steps to make it accessible.

Keyboard navigation is not just for nerds

We often hear about “keyboard warriors” who are proud to leave their mouse in a drawer and do everything with a keyboard. But they are not the only ones using this means of navigating through the app.

Screen readers, once again, are doing the same thing. At least, they use the same “infrastructure” to make sense of navigation within your app. Your browser powers the Tab key on your keyboard the same way a screen reader powers its own navigation: it creates a sorted list of elements you can access and navigate to, keeps track of which elements are disabled in the current context (e.g., focus lock within a modal), and jumps from element to element in order.

If your application cannot be used easily with a keyboard, it cannot be used easily with a screen reader. Therefore,

it is important to ensure elements can be accessed in a coherent order (with tabindex if necessary), that proper

focus locks are in place (cannot go to elements behind a modal screen), that proper semantics are in place, etc.

Explicit navigation with URL change

This is something that especially applies to all the SPAs out there. As in-browser routing became popular, some apps started “masking” navigation behind internal state rather than the “traditional” way of navigating to a new URL. That’s bad.

It doesn’t tell the navigator (and accessibility tools) that navigation occurred. This means that accessibility tools cannot react accordingly, and it also means the URL isn’t sufficient on its own to know where you are in the app, which is bad for user experience.

In the vast majority of cases, the user expects a page reload to bring them to the same page they were on before refreshing. Except if the navigation information is stored internally in your app, you effectively lose everything! Navigation is rolled back, and the user has to go back to where they were. This also affects shared links: the link does not point where the user thinks it does, further causing friction while navigating in your app.

Further things to consider

Despite already being quite long, the list of things I gave is only some of the basics, and there are many, many more things to consider. Here’s a still-non-exhaustive list of additional things to consider:

- Responsive web design counts as accessibility. Making your application scale will make it behave correctly on many devices (not everyone has access to a computer), many screen resolutions (some don’t have the luxury of considering 16:9 1080p a minimum), etc.

- Localizing your application is also making it accessible to foreign individuals. I recommend this blog post from Tolgee about the Benefits and Challenges of Software Localization. (disclaimer: I am a collaborator on the project).

- The weight of your app (JS bundle sizes, image optimizations, etc.) counts as accessibility. People with metered and/or slow connections will struggle to access an application that loads 10 MB of JavaScript.

And the list goes on. Thankfully, you don’t need to be perfect. You may not need to deal with an international audience, or be in a case where providing your website in English is sufficient. And, while some components are extremely hard to get right and accessible, we have here a case of “somebody else did it better than you”.

Component libraries to the rescue

Component libraries are building blocks you can use to create interfaces with complex and interactive elements, such as tabs, highly customized form elements, tooltips, toasts, modals, and pretty much anything you might have to use in your app. The most useful part is that nowadays, a lot of them handle accessibility for you out of the box.

It’s tempting to just roll your own, and assume you can do so without too much risk. You’d have considerably better control over it and not have any problems with limitations. Though in reality, you shouldn’t. Developers of UI kits spent thousands of hours (yes, thousands) building accessible components that actually work. You probably don’t want to spend this much time writing a simple component, do you?

Modern components allow for great customizability, and most UI kits out there are highly customizable. You shouldn’t encounter any limitations, and if you do chances are you are in a case of an antipattern, or the library is constraining you for accessibility purposes. Which is good.

There is one thing that may be a concern: styles. A lot of UI kits, such as Material UI, come with a predefined style (in this case, Material Design). Having a predefined design language can be good, as these design languages have a lot of pre-defined things, and you can quickly build things that look good. They usually have a way to add styles on top of them, which is enough to customize them to suit all your needs.

But, if you’re like me, you may not like this. Or you want to build an app that has its own design language and its own brand. In this case, what you’re looking for is Headless UI libraries.

Headless UI libraries

Headless UI libraries, such as Radix UI, sit in a spot where their sole purpose is to provide components with predefined behavior, and accessibility concerns already taken into account, and then leave everything else up to you. You can think of them as a classic HTML elements, without styles, or anything.

This is a sweet spot of being low-level enough to fit in any single application, but abstracts away a lot of behavior and accessibility concerns out of view, so your app is accessible by default.

Radix isn’t the only one, but it’s my favorite. There are a few other alternative libraries, all with their pros and cons. While I personally fell in love with Radix, you might want to check these out:

- Headless UI, especially if you’re using Tailwind

- Reach UI, at the time of writing their website is… yeah. But it’s a good library nonetheless!

- React Aria by Adobe

- Realkit

- ariakit

- …and many others I didn’t mention here!

You may also want to check shadcn/ui for beautiful components built with Radix and Tailwind. It’s not developed as a package, but rather as things you can copy/paste into your code, so you can use it as a starting block and customize it to your specific needs.

Beyond software engineering

Accessibility topics go beyond software engineering and are something you, the reader, can contribute to even if you’re not writing software.

In the next part of this series about accessibility, I will be tackling how everyone can contribute to making the Internet more accessible. Yes, everyone! Some things happen, especially on social media, which negatively affect accessibility. By raising awareness and correcting certain behaviors, we can make sure the Internet is more accessible.

Want to be notified when the next episode is out? Join my Discord server, and get the “blog updates” role to be notified, or follow me on Twitter!